Home | Research | Crabb Robinson | East End | Code | Publications | Teaching | Awards | Contact

A personal note

The following grew out of a desire to write a comprehensive history of the literature from and about the East End of London. The project is on hold for the time being and as it stands can hardly claim comprehensiveness, yet still I thought I should share what I have got with anyone who might be interested. For details of my seventeen related contributions to Kevin A. Morrison’s Encyclopedia of London’s East End (2022), please see publications. Any suggestions or corrections will be gratefully received and duly acknowledged.

A history

East End literature encompasses novels, memoirs and nonfiction, plays, short stories, and poems. Despite the increasing prominence of the East End in English Literature and related criticism since the work of Charles Dickens, no comprehensive study of it has as yet been undertaken. The need for such a study arises out of the following constellation: historically speaking, the East End is the part of London most shaped by poverty and migration. The area hence has often figured in works of literature as a microcosm of infinitesimal living spaces, overcrowded and alien, alluring yet menacing, a kind of illegitimate underbelly to the national centre of wealth and culture that is the City of London. From within this twofold disenfranchisement of destitution and foreignness, however, has emerged a unique cosmopolitan and emancipatory genre of East End Literature that has so far gone unappraised. Numerous writers from migrant and labouring-class backgrounds have shaped this genre, yet have been excluded from the English literary canon. A Literary History of London’s East End hence must be a counter-history, contesting notions of the discipline’s self-containment around its domestic centre of cultural and material power, and opening up a new dimension to literary and comparative studies. Conversely, such a History should revisit in order to revise English literary history through a narrow yet momentous geographical lens.

The geography

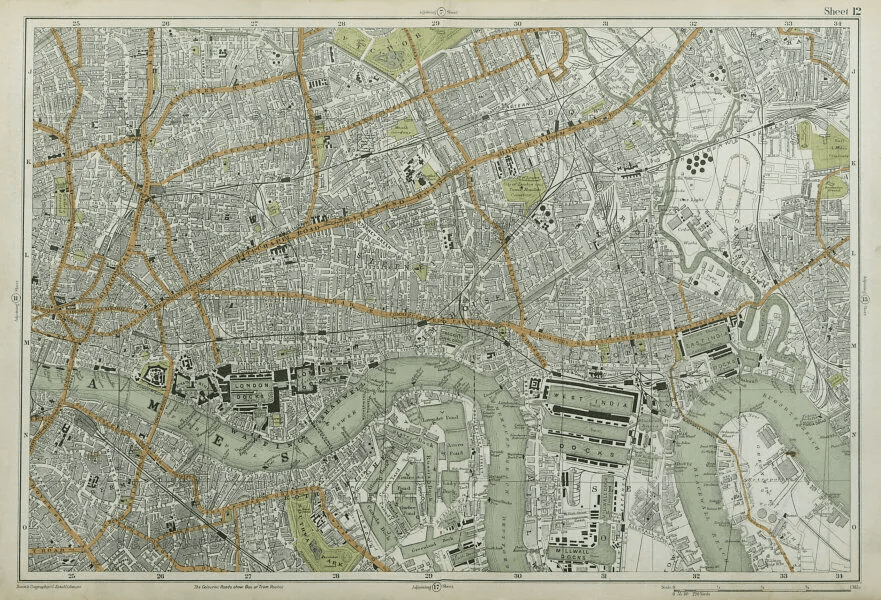

In geographical terms, London’s East End is defined by Aldgate (named after the easternmost gate in the Roman City wall) to the west, the River Thames’s docklands to the south, and the boroughs of Hackney and Waltham Forest to the north. Its eastern boundary has always been the expanding City limit. Migration to the East End has ranged from Huguenot silk weavers’ settlements in Spitalfields in the late-seventeenth century and their Irish tradesfellows thereafter; to continental European Jews fleeing pogroms and genocide between the mid-nineteenth and the mid-twentieth century; to Chinese seamen and launderers in the decades prior to Word War II; to Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi immigrants from parts of the former Empire thereafter (Marriott, 76, 80-1, 223, 275-6, 334-7). These are only the most dominant foreign ethnicities, trends, and trades, while migration to the East End has also encompassed many a British incomer throughout all of these periods. Mary Wollstonecraft’s grandfather, for instance, a labourer from rural Lancashire, was among them. The vast majority of these new arrivals had in common their poverty, resultant disenfranchisement, and need to rely on their wits and labour to scrape a living. Several book-length histories of the East End exist that explore this: William Fishman carried out the most pioneering work, and his East End Jewish Radicals 1875–1914 (1975) and The Streets of East London (1979) influenced not only Alan Palmer’s The East End: Four Centuries of London Life (1989) and John Marriott’s Beyond the Tower: A History of East London (2011), but also Rachel Lichtenstein and Iain Sinclair’s Rodinsky’s Room (1999), a genre-defying account of personal quest into Jewish East End immigrant identity and its Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian roots. Still, there exists as yet no history of the literature that has sprung from this unique constellation.

Tower Hamlets is the London borough covering most of the inner East End, including Whitechapel, Spitalfields, Mile End, Limehouse, Poplar, Wapping, Shadwell, Stepney, and Bethnal Green. A vast, 500-year portion of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives relating to local communities was made available online not long ago – click here for more. Whitechapel Library regularly functioned as a shelter and autodidactic resource for many a local author after its inception in 1892; I expect there to survive undiscovered archival clues as to the reading and writing practices of these authors (few of whom have entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Designated East End archives at Bishopsgate Institute (special collections), the Jewish Museum London, London Metropolitan Archives, and Guildhall Library, as well as smaller local institutions such as the East London People’s Archive (Eastside Community Heritage), Hackney Archives, and Newham Archives and Local Studies Library (Stratford Library) hold further relevant clues, which I envisage to serve as the project’s empirical backbone.

Forging an idea

The closest that scholarship has come to a book-length History of East End Literature is Paul Newland’s The Cultural Construction of London’s East End: Urban Iconography, Modernity and the Spatialisation of Englishness (2008). Taking a sweeping cross-media approach, Newland argues that, since the Victorian period, the East End has emerged from works of literature and film as an enduring atavistic myth. Writers have supposedly nurtured, amplified, and pandered to the fears and prejudices of an English middle-class readership by constructing an idea of Eastenders as depraved, resistant to improvement, and prepared to subvert cultural, material, and moral standards. Newland’s argument is as conclusive as his method, scrutinising outsiders’ perspectives, is selective: the exceptionally rich tradition of Jewish East End writing initiated by Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto (1892), for instance, does not exceed one footnote (87-8 n.11). Nor does Newland mention a single work that originates within the East End’s Muslim communities. His discussion of books about this community consists of a comparison of two novels by authors with strong English middle-class ties (231-48) – Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses (1988) and Monica Ali’s Brick Lane (2003). Hence, while Newland persuasively observes that a forged idea of the East End ‘has often functioned in very similar ways to the Orient’ (25), his selective cross-media approach omits a significant number and variety of local voices. This is no criticism of the author and his work, but rather an acknowledgement of the inevitable limitations in scope even of book-length studies.

Chaucer to Dickens

Geoffrey Chaucer from 1374 lived and worked at Aldgate (The Canterbury Tales, xxix). In the ‘General Prologue’ to The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer mocks Bow school and its fictional alumna, the Prioress, as, respectively, teaching and speaking elegant but incorrect French (6). Another literary milestone here is Thomas Nashe and Ben Jonson’s play The Isle of Dogs (1597 – staged at the Swan Theatre but now lost), which drew immediate government censorship for its ‘very seditious and slanderous’ content, and saw Jonson imprisoned (Birch, 541). Daniel Defoe was a member of the Dissenting community at Newington Green, to which Mary Wollstonecraft would later belong also. Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year (1722) describes Aldgate as a temporary refuge during the outbreak of the bubonic plague in 1665; contributed to a developing notion of the area; and informed the character of Nicholas Dyer in Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor (1985): Dyer, whose historical equivalent is the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, as a child witnesses the Great Plague, is orphaned by it, and develops those dark character traits that drive the plot of Ackroyd’s novel across three centuries amid its East End setting.

Limehouse’s notoriety as a crime hub shot through with opium dens is based not least on Dickens’s final, unfinished novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). The book features one such den, as does Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’ (1891). Yet the beginnings of this date back much earlier. Thomas De Quincey, author of Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), had a considerable stake in the East End. His essay ‘On Murder, Considered as one of the Fine Arts’ (1827), based on the 1811 Ratcliffe Highway murders between Wapping and Limehouse, treats the relationship between crime and aesthetic performance. De Quincey thereby became the trailblazer for later crime fiction about the East End and beyond, for example Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). Notably, De Quincey’s Confessions were published in the same year as the first printed mention of the term ‘East End’, in Pierce Egan’s novel Life in London (1821) (Newland, 47). The genre was yet to unfold and claim its label from within. A notion of the hamlets east of the City Wall thus began to require the distinct signifier ‘East End’ around 1821, while writing about the area from the outside predominated. De Quincey’s early literary explorations of Limehouse suggest that disrepute, threat, and addiction had been a staple of writing about the locality since before the establishment of the Chinese community. Asian otherness was a layer of alienation added and exploited by certain later writers, most disagreeably Sax Rohmer (more below).

Victorian slum fiction

In the course of the nineteenth century, the East End grew from a motley set of suburban villages and hamlets into, arguably, Europe’s most deprived and notorious urban slum. Fishman’s centenary of the most infamous year, East End 1888: A Year in a London Borough among the Labouring Poor (1988), reveals a cross-section of this development. The book draws attention away from the 1888 Ripper murders to the area’s broader social history. Amidst this, the 1880s saw the beginnings of the late-Victorian craze for East End slum fiction, about a local underclass beneath the working poor. This craze occurred in the wake of Walter Besant’s novel All Sorts and Conditions of Men (1882), comprised as its most famous specimen Arthur Morrison’s A Child of the Jago (1896), and continued until at least The Hole in the Wall (1902), also by Morrison. Morrison (1863–1945), born locally, in Poplar, has been at the centre of renewed critical attention of late, most notably in Eliza Cubitt’s Arthur Morrison and the East End: The Legacy of Slum Fictions (2019), which sees his work as resisting the kind of appropriative middle-class myth-creation elaborated by Newland. Yet more recently, Diana Maltz’s collected volume Critical Essays on Arthur Morrison and the East End (2022) has surveyed a broad variety of aspects across Morrison’s work. Janssen and Robertson’s collected volume Margaret Harkness: Writing Social Engagement 1880–1921 (2019) reveals the ways in which the works of Margaret Harkness (1854–1923), who wrote under the nom de plume ‘John Law’, criticise abuses of power in relation to the East End, both at a personal and institutional level. George Gissing, author of The Unclassed (1884), has received critical attention too, most notably in Emma Liggins’s monograph George Gissing, the Working Woman, and Urban Culture (2017). Kevin A. Morrison’s Walter Besant: The Business of Literature and the Pleasures of Reform, published in 2019 also, makes a compelling case for the reciprocity of Besant’s pioneering roles as a hands-on social reformer and prolific author of fiction. The same Kevin A. Morrison has recently published The Encyclopedia of London’s East End (2022), to which I have contributed seventeen entries, totalling 11,000 words, on literary, cultural, historical, and geographical subjects. A list of these entries can be found under publications.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, local writers began to claim the concept ‘East End’ and its concomitant genre from within. The most prominent literary cornerstones are Besant’s All Sorts and Conditions of Men; Arthur Morrison’s Tales of Mean Streets (1894), A Child of the Jago, and The Hole in the Wall; William Morris’s utopian News from Nowhere (1890); and Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto and The Big Bow Mystery (1892). Morrison’s portrayal of the ‘Jago’ slum, based on the Old Nichol Street Rookery off Shoreditch High Street, at first glance appears as a kind of slapstick zoo perspective on a Darwinist microcosm of struggle and the survival of the fittest, in which characters are being condescended to and their very humanity is put at stake. Upon closer inspection, though, Morrison thus retreats from custodianship over emotional responses, freeing his work from moral didacticism and engendering a deeper and more direct reader engagement. Still, Zangwill emerges as the true pioneer here, because he had, four years earlier and for the first time, begun to open up the Jewish community to outside readers in ways that disclosed its abject poverty but upheld its dignity.

Further contemporaneous works of East End slum fiction include William Black, Shandon Bells (1893); J. Dodsworth Brayshaw, Slum Silhouettes (1898); John Le Breton, Unholy Matrimony (1899); Joseph Hocking, All Men Are Liars (1895) and The Madness of David Baring (1900); Katherine Douglas King, The Scripture Reader of St. Marks (1895) and Father Hilarion (1897); Harry Lander, Lucky Bargee (1898); Henry Nevinson, Neighbours of Ours (1895); Richard Orton Prowse, A Fatal Reservation (1895); Morley Roberts, Maurice Quain (1897); John A. Steuart, Wine on the Lees (1899); and the post-apocalyptic After London; Or, Wild England (1885) by Richard Jefferies, in which looting Eastenders are portrayed as not only foreign but zoomorphic in both appearance and conduct. A trilogy by Margaret Harkness (1854–1923), in contrast, calls out contemporary vilification of destitution, foreignness, and immigration in the late Victorian period: A City Girl (1887), Out of Work (1888), and In Darkest London […] Captain Lobe: A Story of the Salvation Army (1889). (The Salvation Army was founded in the East End in 1865.) The bleak realism of George Gissing’s The Unclassed is another instance of late-Victorian slum fiction.

From traditions to genre

In the first half of the twentieth century, the East End became a contested ideological battleground and field for political experimentation. This is reflected in the various educational and publishing activities of the German Philo-Semite, anarchist, and trade unionist Rudolf Rocker, high-profile visiting politicians such as Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin, and Oswald Mosley’s attempts, thwarted at the 1936 Battle of Cable Street, to exploit the area’s social tensions for his British Union of Fascists. Also, while overpopulation and squalor contributed to the authorities’ neglect of the area and crime thrived, the East End became a haven for sexual transgressions that were still illegal at the time (homosexuality) or widely disapproved of (miscegenation) (Sandhu, 7, 25, 105). Cohen hence finds that ‘no area in Britain has been more written about, more exploited as a source and site for the projection of public anxieties about the proletarian combination or sexual promiscuity, the state of the nation or the degeneration of the race’ (173). Such insights, partially valid as they are, inform Newland’s central claim about a British national culture appropriating the East End in order to find an imaginary habitat for its own apprehensions. Nadia Valman’s on-going work, on the contrary, leaves no doubt that certain key strands of East End writing have long outweighed such fear-mongering. Among other work on the Jewish East End, Valman co-edited, and contributed to, The ‘Jew’ in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Culture: Between the East End and East Africa (2009). She has also demonstrated that Zangwill’s contributions to Victorian literature were a great deal more refined and progressive than hitherto acknowledged: Valman’s article ‘The East End Bildungsroman from Israel Zangwill to Monica Ali’, for instance, makes a strong case for Children of the Ghetto reverberating in Brick Lane and its fictionalisation of Bangladeshi immigrant hardship (3). Such Victorian echoes in contemporary literature, according to Valman, do not owe to British cultural dominance being reproduced and submitted to, but to an autonomous tradition of immigrant betterment, and the Bildungsroman genre as its vehicle, that defies cultural appropriation.

Jewish East End literature

The Jewish East End literary tradition gathered momentum in the early twentieth century. Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918) was born in Bristol but brought up in Stepney, which left a lasting mark on his poetry collection Youth (1915) and his pastorals from the trenches of World War I. Simon Blumenfeld (1907–2005), Willy Goldman (1910–2009), and Emanuel Litvinoff (1915–2011) were all native Eastenders from immigrant working-class backgrounds. They each left school at fourteen to toil in local tailoring sweatshops, became autodidacts (often reading in Whitechapel Library), and together formed a writers’ circle in the nineteen-thirties (Rubinstein et al, 107). Blumenfeld’s novel Jew Boy (1935) drew immediate public attention and critical acclaim. It may feature a steadfastly Communist hero, but the portrayed marches, protesting against the treatment of Jews in Germany, pick up on any fears of a foreign, proletarian inundation in order to undo them. They are part of a steady to-and-fro between east and central London throughout the novel that opens up confined East End space for face-to-face encounters. The realism of Goldman’s works, especially East End My Cradle (1940), is generally bleaker and more spatially confined, though no less integer and profound. Litvinoff wrote more experimentally during these years, and lived through the personal, political, and religious struggles that came to inform his later Journey Through a Small Planet (1972). Litvinoff destroyed much of his experimental pre-World War II work. Blumenfeld’s novels Jew Boy, Phineas Kahn: Portrait of an Immigrant (1937 – about the family his wife Deborah, a second-generation immigrant and Cable Street native), and They Won’t Let You Live (1939) shaped this period of East End Literature, as did his early career as a playwright with the Hackney-based Rebel Players.

Modernisms of abjection

East End Literature between the turn of the twentieth century and World War II became a trailblazer for an eclectic range of egalitarian, mostly labouring-class modernisms. Nowhere else in Britain was the fragmentation of modern life felt more intensely than amidst the heavy machinery of the docks, the countless tailoring sweatshops competing in a remorseless market, and the melange of displaced people with the array of foreign impulses that they were bringing to the area. A growing number of East End writers, predominantly Jewish, began to explore this fragmentation in subjective and often disjointed memoirs, novels, poems, and plays. A clear line between late-Victorian slum fiction and modernist innovation cannot always be drawn, as several of the above-mentioned works of slum fiction contain quasi-modernist avant-gardist elements. Zangwill’s and Arthur Morrison’s later works, such as The Melting Pot (1909) and Green Ginger (1909) respectively, are further points of reference where the transition of literary epochs is concerned. The poetry of Rosenberg and Wilfred Owen (1893–1918) are subsequent cornerstones. Both men are famous primarily for poeticising World War I (in which both were to die). Still, the East End left a lasting imprint on their works: Owen, in ‘Shadwell Stair’, for instance, wrote allegorically about his homosexual experiences around local docks and warehouses. Unlike Rosenberg, he came from a middle-class family from rural England. East End life was not a material given but a choice to Owen, precipitated by his desire to live out his sexual orientation.

Limehouse Chinatown

Parallel to the evolving Jewish tradition runs a strand of English East End writing whose hegemonic claims appear to have remained unchallenged from within the foreign community that it targeted – namely works about the Chinese settlement amid the Limehouse docklands. The most popular of these works were Sax Rohmer’s thirteen Fu Manchu novels, from The Mystery of Dr Fu Manchu (1913) to Emperor Fu Manchu (1959), and to a lesser extent also Thomas Burke’s short-story collection Limehouse Nights (1916) and its sequel More Limehouse Nights (1921). Critical opinion on Rohmer’s series, in which the eponymous villain plots world domination from his East End base, is conclusive: Seed calls Rohmer’s works ‘appalling’ (58); Donald labels the first volume ‘one of the most dementedly racist works in English popular literature’ (173); and Mayer stresses seriality as a key feature in cementing western fears. Critical opinion on Burke is less consensual. Newland situates him, too, amidst the insidious Orientalist and more overtly racist ‘Yellow Peril’ discourses (110). The latter emerged around the turn of the century from perceived fears in the west of Chinese and Japanese ascendancy; Christopher Frayling’s The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & The Rise of Chinaphobia (2014) explicates this, corroborating the above-quoted verdicts on Rohmer while advancing more nuanced takes on Burke. Witchard, in Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie (2016), interprets Burke yet more favourably as picking up his readers at their points of prejudice in order to subtly undo these. In Burke’s ‘The Chink and the Child’ (Limehouse Nights), to illustrate, the Chinese protagonist debased in the title emerges as morally upright and in defined contrast to the physically and racially abusive English father of an East End girl.

Various spin-offs about Limehouse Chinatown, such as Edgar Wallace’s The Yellow Snake (1926) and Agatha Christie’s The Big Four (1927), were published in the wake of Rohmer and Burke’s popular successes. An intriguing thought in this context is whether any archival materials – informal pieces of life-writing such as letters, diaries, or miscellaneous draft papers, perhaps even extant manuscript works of literature or neglected publications – survive that originate within the Chinese community and resist cultural appropriation. Granted, this may sound somewhat far-fetched, but if true may revolutionise our understanding of Limehouse Chinatown, its cultural exchanges, and literary representations. Seed’s and Case’s studies after all suggest that the Chinese community was not particularly closed off and interaction with its environs frequent.

The inside–outsider memoir

Clement Attlee (1883–1967), the future Prime Minister, wrote ‘Limehouse’ in 1912. The poem focuses on the struggling workers there, many of them children, and their lives on the breadline. It ends in a vision of collective material safety and emancipation. Jim Crooks’s Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way (2012) fictionalises early Labour Party and Fabian Society activism around Limehouse, Poplar, and the Isle of Dogs prior to Attlee. The appalling living conditions that Attlee and Crooks address emerge in further detail from two early-twentieth-century works of non-fiction. The American Jack London spent part of 1902 in Whitechapel, which led to a new strand of East End Literature, namely the memoir of the sympathetic middle-class outsider ‘going native’. London recounts these experiences in The People of the Abyss (1903), which three decades later prompted George Orwell to revisit the area for Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). Daniel Farson’s Limehouse Days (1991) and Tarquin Hall’s Salaam Brick Lane (2005) demonstrate that this inside–outsider strand has been thriving ever since. Again, it would be too simplistic to speak of appropriation of the foreign and the poor in such memoirs, as these memoirs seek to assert the integrity of the East End in all its abjection. Farson’s criticism of progressing gentrification is one case in point, echoing similar concerns in Penelope Lively’s City of the Mind (1991) and anticipating Iain Sinclair’s self-conscious recent work as outlined below

Branching out and into the postmodern

After World War II, the East End’s ethnographic changed perceptibly. Much of the Limehouse docklands had been destroyed in bombing raids, and the Chinese community moved to its present location in Soho. The majority of East End Jews followed the by then established trend of relocating to north London, but some chose to settle, along with Eastenders of British ancestry who had acquired the necessary means, further east, in suburban and rural Essex. Jewish authors such as Alexander Baron (1917–1999), Wolf Mankowitz (1924–1998), Bernard Kops (b.1926), Harold Pinter (1930–2008), Eric Jakob (b.1939), and Rachel Lichtenstein (b. 1969) have nonetheless continued to write about the East End, and shape the genre, to the present day. Baron’s novels, most prominently With Hope, Farewell (1952) and The Lowlife (1963), continue Blumenfeld’s geographical and personal opening-up of the Jewish community towards other local minority groups, and into central London. The plot of The Lowlife hence ‘ranges from local racetracks to the middle-class suburbs, from seedy slums to swinging sixties Soho, and was one of the first British novels to include Caribbean immigrants among its characters’ (William Baker 2004). The final chapter of Jew Boy does so, too. Baron’s Strip Jack Naked (1966) extends these centrifugal narratives towards the European continent, as does Lichtenstein’s work. Baron grew up in Stoke Newington, on the East End’s fringes, and served in World War II. His first novel, From the City, from the Plough (1948), blends these experiences. The recent collected volume edited by Thomas, Whitehead, and Worpole, So We Live: The Novels of Alexander Baron (2019), contains pioneering critical approaches to Baron, one by Valman. Kops has received profound but underrated critical treatment in Baker and Roberts Shumaker, Bernard Kops: Fantasist, London Jew, Apocalyptic Humorist (2013).

Self-reflexive novels, memoirs, poems, and plays about the East End written in the decades after World War II, often to be classed as postmodern, advance the resilience and hybrid cultural integrity of the East End literary genre. Marcan’s self-published An East End Directory: A Guide to the East End of London with Special Reference to the Published Literature of the Last Two Decades (1979) here serves as an invaluable literary signpost to these years of ethnographic transition. Goldman’s literary career functions as a point of departure, with a re-assessment of Cunningham’s point that ‘Socially observant, satirical, […] [Goldman’s] prose volumes make him a precursor of the Angry Young Men’ of the nineteen-fifties. Goldman’s writings encompass, among other works, East End My Cradle, The Light in the Dust (1944), A Start in Life (1947), and A Saint in the Making and Other Stories (1951). Blumenfeld’s later work, for instance the plays The Promised Land (1960, in Yiddish) and The Battle of Cable Street (1987), provide insightful points of comparison, as do works by Bernard Kops, such as The Hamlet of Stepney Green (1957), and by the Nobel Prize winning East End dramatist Harold Pinter. Pinter’s The Caretaker (1960), for one, thematises isolation amidst kinship bonds in ways that anticipate the central figure in Rodinsky’s Room, a hermit who looked after the Princelet Street synagogue. Mankowitz’s oeuvre, comprising A Kid for Two Farthings (1953), an autobiographical novel about youth, resourcefulness, and hope in Spitalfields, fits the mould, as does Baron’s and related criticism listed above. Jason Finch’s claim that Litvinoff’s work may ‘seem a guerrilla force or underground resistance movement in relation to an “elite” minority culture embodied by the likes of [T.S.] Eliot and F.R. Leavis’ (215) deserves consideration in this light: Litvinoff’s work, from the poetry collection Conscripts: A Symphonic Declaration (1941) to his renewed engagement with his East End roots in Journey Through a Small Planet and A Death out of Season (1973), is emblematic of the resilience and hybrid cultural integrity of East End Literature.

Conflict or mutuality?

Since the mid-twentieth century, new arrivals to the East End have predominantly come from Asian parts of the former British Empire, and from Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu backgrounds. Naturally, it took some time for these new communities to raise their English authors, but raise their English authors they would. These authors in turn have left their mark on East End Literature, acting as further catalysts for the genre. Sandhu’s London Calling: How Black and Asian Writers Imagined a City (2004) is a milestone study of Afro-Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi authorship across the capital. References to the East End are scarce, however, and in need of complementing and updating. Although Sandhu anticipates Newland insofar that city spaces are always also imagined spaces, Sandhu’s conclusions preempt Newland’s: ‘The “metropolis” […] does not always feel imperilled by, or hostile to, “marginal” culture. […] individuals (such as Laurence Sterne) and institutions (such as the BBC) have traditionally been very keen to encourage marginal voices’ (Sandhu, 14). The benefit, writes Sandhu, has been mutual, shared between domestic and immigrant cultures. London Calling proves the validity of such claims through its prescience, for instance with respect to Bernardine Evaristo (Sandhu, 243–4). Evaristo grew up just across the Thames from the East End’s Royal Docks, and in 2019 became the first person of Afro-Caribbean descent to win the Booker Prize.

New voices

Ed Husain’s The Islamist: Why I Joined Radical Islam in Britain, What I Saw Inside and Why I Left (2007), part Bildungsroman andpart memoir, was inspired by the author’s upbringing among the Asian communities of Whitechapel, Stepney, and Mile End. Suresh Singh’s A Modest Living: Memoirs of a Cockney Sikh (2018) is an experimental family biography. Singh’s father had migrated to Spitalfields from the Punjab in 1949, and the family lived in the same house in Princelet Street for seventy years thereafter. (The street also features in Rodinsky’s Room as home to the Princelet Street synagogue.) Mohsin Zaidi’s acclaimed A Dutiful Boy: A Memoir of Secrets, Lies and Family Love (2021) in its first edition was subtitled A Memoir of a Gay Muslim’s Journey to Acceptance (2020). ‘Acceptance’ here means, and continues to do so in the second edition, the acceptance of one’s sexual orientation as an unchangeable given, rather than the acceptance of the narrator’s Pakistani immigrant ancestry, dark skin, and Shia Muslim faith by a dominant English culture. Zaidi’s narrator criticises homophobia amid his familial nucleus just as much as casual racism within the LGBT community, while, despite such struggles, being determined not to let go of either circle. Oliver von Knebel Doeberitz published a book chapter entitled ‘Muslims against Gays? Faith, Sexuality, Resistance and London’s East End’ (2018), which is a prescient exploration of the constellation from within which Zaidi writes.

Psychogeography and gentrification

East End writing by authors of British ancestry, too, often resists cultural and material appropriation. One case in point is Iain Sinclair’s self-critical turn against the tradition he had shaped himself – East End psychogeography. The aesthetic theory and practice of psychogeography, respectively, investigate and apply the ‘emotional and behavioural effects of the environment’ (Phil Baker, 323). Sinclair (b.1943) explored the uncanny in East End spaces along such lines in Lud Heat (1975) and Suicide Bridge (1979). Yet gentrification of the East End gathered pace during these years, when economic deregulation under Thatcher turned London into a boomtown while exacerbating social divisions and undermining working-class cohesion across the country (Haywood, 139). With that came the commodification of the East End, and Sinclair found that his work was inadvertently contributing to it, by making the area ‘cool’ – which is to say, palatable for the agents of cultural appropriation. Sinclair’s more recent literary perambulations, for instance in Downriver and London Orbital (both 2002), therefore politicise more soberly the prevailing hardships of poverty and neglect as perpetuated through property developing, transnational investment, and the pricing of locals out of their neighbourhoods.

East End Literature here is overtly playful and eclectic, often in the shape of postmodern engagements with the area’s past that were published in the nineteen-seventies and -eighties, most prominently Sinclair’s Lud Heat, Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor, and Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. The former two accentuate the interplay between postmodernism and psychogeography, as Lud Heat’s exploration of the occult in the architecture of east London’s Hawksmoor churches influenced Ackroyd. One key stylistic device by means of which Ackroyd merges psychogeography and postmodernism is pastiche, in an honorific imitation of Defoe’s Journal and within the genre in question. Rushdie’s postmodernism is less concerned with psychogeography (his fictionalisation of the East End encompasses Southall in west London, which arguably places him in the centrifugal tradition of Blumenfeld and Baron) than it is with local immigrant identities. Rushdie’s narrative technique of the ‘broken mirror’ is nonetheless a key postmodern device of fragmentation and indecision that sidesteps cultural appropriation.

Contemporary defiance

A growing awareness of its own significance has prompted not self-indulgence but a self-critical turn in East End Literature. This self-critical turn has enabled foreign influences to keep infiltrating, shaping, and innovating the genre. The popular novels of Gilda O’Neill, from The Cockney Girl (1992) and Whitechapel Girl (1993) to Of Woman Born (2005), provide an Anglo-Irish working-class feminist insider’s perspectives on an East End increasingly transformed by gentrification and property development. The changed focus of Sinclair’s recent work as explained above with respect to Downriver and London Orbital add a further dimension in this context: Sinclair, long-term resident of east London, has in recent years consciously shaped an East End psychogeography of defiance that joins forces with multi-ethnic insider perspectives from Zangwill to Zaidi. Sinclair’s collaboration with Lichtenstein on Rodinsky’s Room in the late nineteen-nineties underscores this shift, as Lichtenstein’s quest into the mystery of Rodinsky’s disappearance leads her to discover East End spaces, their eastern European Jewish inspirations, and their prevailing influences on present-day community life. Kops’s memoir Bernard Kops’s East End (2006) and Eric Jakob’s Just a Boy from London’s East End (2007) likewise offer retrospective accounts of individual and communal events in the area. Husain’s The Islamist here forms a striking contrast insofar as it was written by an author from a different generation and East End community. Yet Husain’s eventual discovery of liberal Sufi speculation, though starting out from a more entrenched state of mind, nevertheless provides an intriguing philosophical parallel across religious schisms with Lichtenstein’s gradual endorsement, in Rodinsky’s Room, of cabalistic mysticism.

Ali’s bestselling Brick Lane here emerges as a specimen of the immigrant Bildungsroman leading up to the discovery of female agency and the rebuttal of notions of fate that had been imbibed since early childhood. Suresh Singh’s A Modest Living, too, and the communities that it describes, continues the hybrid cultural integrity of Litvinoff’s Journey, paying homage to humble cross-cultural inclusiveness in the East End as well as liberal Englishness. Singh’s book does so in defiance of the wealth and power of the adjacent City as insufficient signifiers of home culture. In line with Sandhu’s claims quoted above, the Singh family found the East End a congenial environment, which led to coining the phrase ‘Cockney Sikh’: the son of Indian immigrants assimilated into local working-class culture to the point of joining the punk scene in the late seventies, albeit without disowning the family’s cultural heritage and hence endorsed by his parents in return. Zaidi’s A Dutiful Boy underscores Valman’s observation of immigrant aspiration, and it does so alongside the author’s acute awareness of the destructive joint forces of cultural and material appropriation. The book recounts the author’s attending East End state schools, winning a place at Oxford, and starting a career as a lawyer specialising in white-collar crime. As such, A Dutiful Boy is the momentary culmination of emancipatory East End Literature.

Diversities

Ethnic and cultural diversity lie at the heart of East End Literature. But the literary subversion of sexual heteronormativity also plays a significant part in it, most prominently so in the works of Wilfred Owen, Oscar Wilde, Peter Ackroyd, and Mohsin Zaidi. The latter’s A Dutiful Boy continues various emancipatory strands of East End Literature, not only with respect to class and ethnicity but also homosexuality and gender roles. The homosexuality of Nicholas Dyer in Hawksmoor, set off by the book’s openly gay author, fleshes out the earthliness of a central antagonist in the tradition of Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Wilfred Owen chose the East End in order to live out his sexual orientation, then wrote about it. Oscar Wilde, in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), had previously explored a similar territory – middle-class visitors leaving behind their accustomed social personae and indulging homoeroticism and homosexuality upon entering the East End. The date of publication here is no coincidence – it falls within the twenty-year trend for East End slum fiction in the wake of Besant’s All Sorts and Conditions of Men. This first proliferation of East End writing prompted authors, both from within and outside the area, to expand and consolidate the young genre’s emancipatory dynamism by countering appropriative heteronormativity.

Overlaps and interfaces

The Literary History of London’s East End is thus situated at the crossroads of scholarly discourses on class, urban space, race/ethnicity, and resistance to hegemony. These fields and their overlaps have drawn renewed scholarly attention in recent years, for example in Ehland and Fischer’s collected volume entitled Resistance and the City: Negotiating Urban Identities: Race, Class, and Gender (2018). My paper at the conference ‘British “Fictions of Class” since 1945 – Revitalising Class in the Twenty-First Century’ (University of Siegen, online, 18–19 June 2021) focused on narratives of class in the Jewish East End novel (https://fictionsofclass.wordpress.com/programme/), and for the first time introduced the above ideas and observations to an international academic community. The groundwork research that has gone into the above has further enabled me to teach undergraduate and postgraduate courses on East End Literature at the universities of Leipzig, Erfurt, and Hamburg, and to contribute eleven entries (11,000 words in total) to Kevin A. Morrison’s Encyclopedia of London’s East End (2022).

Bibliography

Archives:

Bishopsgate Institute (special collections)

East London People’s Archive (Eastside Community Heritage)

Guildhall Library

Hackney Archives

The Jewish Museum London (designated East End Archives)

London Metropolitan Archives

Newham Archives and Local Studies Library (Stratford Library)

Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives [QMUL affiliation]

Whitechapel Library [QMUL affiliation]

Primary works:

Ackroyd, Peter, Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1994)

—–, Hawksmoor (London: Hamilton, 1985)

Ali, Monica, Brick Lane (London: Black Swan, 2004)

Attlee, Clement, ‘Limehouse’, in Bricklight: Poems from the Labour Movement in East London, ed. Chris Searle (London: Pluto Press, 1980), 50

Baron, Alexander, From the City, from the Plough (London: Cape, 1948)

—–, The Lowlife (London: Collins, 1963)

—–, Strip Jack Naked (London: Collins, 1966)

—–, With Hope, Farewell (London: Cape, 1952)

Besant, Walter, All Sorts and Conditions of Men (London: Chatto & Windus, 1882)

Black, William, Shandon Bells (London: Macmillan, 1893)

Blumenfeld, Simon, The Battle of Cable Street (Edinburgh, 1987)

—–, Jew Boy (London: Cape, 1935)

—–, Phineas Kahn: Portrait of an Immigrant (London: Cape, 1937)

—–, The Promised Land (London, 1960)

—–, They Won’t Let You Live (London: Nicholson & Watson, 1939)

Brayshaw, J. Dodsworth, Slum Silhouettes (London: Chatto & Windus, 1898)

Burke, Thomas, Limehouse Nights: Tales of Chinatown (London: Richards, 1916)

—–, More Limehouse Nights (New York: Doran, 1921)

Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterbury Tales, tr. David Wright, ed. Christopher Cannon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011 [1387–1400])

Christie, Agatha, The Big Four (London: Collins, 1927)

Crooks, Jim, Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way (Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace, 2012)

De Quincey, Thomas, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (Oxford: OUP, 1996 [1821])

—–, ‘On Murder, Considered as One of the Fine Arts’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine XXI (January–June 1827), 199–213

Defoe, Daniel, A Journal of the Plague Year (London: Nutt, 1722)

Dickens, Charles, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (London: Chapman & Hall, 1870)

Doyle, Arthur Conan, ‘The Man with the Twisted Lip’, in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (New York: Harper, 1892 [1891]), 126–52

Egan, Pierce, Life in London (London: Sherwood, Neely & Jones, 1821)

Farson, Daniel, Limehouse Days (London: Joseph, 1991)

Gissing, George, The Unclassed (London and Bungay: Chapman & Hall, 1884)

Goldman, Willy, East End My Cradle (London: Faber & Faber, 1940)

—–, The Light in the Dust (London: Grey Walls Press, 1944)

—–, A Saint in the Making and Other Stories (London: Constellation Books, 1951)

—–, A Start in Life (London: Fortune Press, 1947)

Hall, Tarquin, Salaam Brick Lane: A Year in the New East End (London: Murray, 2005)

Harkness, Margaret [John Law], A City Girl: A Realistic Story (London: Vizetelly, 1887)

—–, In Darkest London […] Captain Lobe: A Story of the Salvation Army (London: Reeves, 1891 [1889])

—–, Out of Work (London: Sonnenschein, 1888)

Hocking, Joseph, All Men Are Liars (Boston: Roberts, 1895)

—–, The Madness of David Baring (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1900)

Husain, Ed, The Islamist: Why I Joined Radical Islam in Britain, What I Saw Inside and Why I Left (London: Penguin, 2007)

Jakob, Eric, Just a Boy from London’s East End (Ware: Eric Jakob, 2007)

Jefferies, Richard, After London; Or, Wild England (London: Cassell & Co., 1885)

King, Katherine Douglas, Father Hilarion (London: Hutchinson, 1897)

—–, The Scripture Reader of St. Marks (London: Hutchinson, 1895)

Kops, Bernard, The Hamlet of Stepney Green (London: Evans, 1959 [1957])

Lander, Harry, Lucky Bargee (London: Pearson, 1898)

Le Breton, John, Unholy Matrimony (London: Macqueen, 1899)

Lichtenstein, Rachel, and Iain Sinclair, Rodinsky’s Room (London: Granta, 1999)

Litvinoff, Emanuel, Conscripts: A Symphonic Declaration (London: Favil Press, 1941)

—–, A Death out of Season (London: Joseph, 1973)

—–, Journey Through a Small Planet (London: Joseph, 1972)

—–, ‘To T.S. Eliot’, in Litvinoff, Journey Through a Small Planet, 194–5

Lively, Penelope, City of the Mind (London: Deutsch, 1991)

London, Jack, The People of the Abyss (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1903)

Mankowitz, Wolf, A Kid for Two Farthings (London: Deutsch, 1953)

Milton, John, Paradise Lost (London: Simmons, 1667)

Morris, William, News from Nowhere; Or, an Epoch of Rest (Boston: Roberts, 1890)

Morrison, Arthur, A Child of the Jago (London: Methuen & Co, 1896)

—–, Green Ginger (London: Hutchinson, 1909)

—–, The Hole in the Wall (London: Methuen, 1902)

—–, Tales of Mean Streets (London: Methuen, 1894)

Nashe, Thomas, and Ben Jonson, The Isle of Dogs (1597)

Nevinson, Henry, Neighbours of Ours (Bristol: Arrowsmith, 1895)

O’Neill, Gilda, The Cockney Girl (London: Headline, 1992)

—–, Of Woman Born (London: Heinemann, 2005)

—–, Whitechapel Girl (London: Headline, 1993)

Orwell, George, Down and Out in Paris and London (London: Gollancz, 1933)

Owen, Wilfred, ‘Shadwell Stair’, in The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen, ed. C. Day Lewis (New York: Chatto & Windus, 1963), 94

Pinter, Harold, The Caretaker (London: Methuen, 1960)

Prowse, Richard Orton, A Fatal Reservation (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1895)

Roberts, Morley, Maurice Quain (London: Hutchinson, 1897)

Rohmer, Sax, Emperor Fu Manchu (London: Jenkins, 1959)

—–, The Mystery of Dr Fu-Manchu (London: Methuen, 1913)

Rosenberg, Isaac, Youth (London: Narodiczky, 1915)

Rushdie, Salman, The Satanic Verses (London: Penguin, 1988)

Sinclair, Iain, Lud Heat: A Book of Dead Hamlets (London: Albion Village, 1975)

—–, Downriver (London: Granta, 2002)

—–, London Orbital (London: Granta, 2002)

—–, Suicide Bridge (London: Albion Village, 1979)

Singh, Suresh, A Modest Living: Memoirs of a Cockney Sikh (London: Spitalfields Life, 2018)

Steuart, John A., Wine on the Lees (London: Hutchinson, 1899)

Wallace, Edgar, The Yellow Snake (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1926)

Wilde, Oscar, The Picture of Dorian Gray (London et al: Ward Lock, 1891)

Zaidi, Mohsin, A Dutiful Boy: A Memoir of Secrets, Lies and Family Love (London: Penguin Random House, 2021 [2020])

Zangwill, Israel, The Big Bow Mystery (London: Henry, 1892)

—–, Children of the Ghetto: a Study of a Peculiar People (London: Heinemann, 1892)

—–, The Melting Pot (London: Heinemann, 1909)

Secondary works:

Baker, Phil, ‘Secret City: Psychogeography and the End of London’, in Joe Kerr and Andrew Gibson (eds), London from Punk to Blair (London: Reaktion, 2003), 323-33

Baker, William, ‘Baron, (Joseph) Alexander’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) <www.oxforddnb.com> [accessed 20 November 2021]

—– and Jeanette Roberts Shumaker, Bernard Kops: Fantasist, London Jew, Apocalyptic Humorist (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2013)

Birch, Dinah, The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 7th edition (Oxford: OUP, 2009)

Case, Shannon, ‘Lilied Tongues and Yellow Claws: the Invention of London’s Chinatown, 1915-45’, in Challenging Modernism: New Readings in Literature and Culture 1914–45, ed. Stella Deen (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), 17-34

Cohen, Phil, ‘All White on the Night? Narratives of Nativism on the Isle of Dogs’, in Rising in the East: The Regeneration of East London, eds. Tim Butler and Michael Rustin (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1996), 170-96

Cubitt, Eliza, Arthur Morrison and the East End: The Legacy of Slum Fictions (London and New York: Routledge, 2019)

Cunningham, Valentine, ‘Willy Goldman’, The Guardian, 6 July 2009 <www.theguardian.com/books/2009/jul/06/obituary-willy-goldman> [accessed 18 January 2022]

Donald, James, ‘How English is it? Popular Literature and National Culture’, in Space and Place: Theories of Identity and Location, ed. by Erica Carter, James Donald, and Judith Squire (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1993), 165-86

Ehland, Christoph, and Pascal Fischer, Resistance and the City: Negotiating Urban Identities: Race, Class, and Gender (Amsterdam: Brill, 2018)

Finch, Jason, ‘London Jewish . . . and Working-Class? Social Mobility and Boundary-Crossing in Simon Blumenfeld and Alexander Baron’, in Working-Class Writing: Theory and Practice, ed. Ben Clarke and Nick Hubble (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 207–28

Fishman, William, East End 1888: A Year in a London Borough among the Labouring Poor (London: Duckworth, 1988)

—–, East End Jewish Radicals 1875–1914 (London: Duckworth, 1975)

—–, The Streets of East London (London: Duckworth, 1979)

Frayling, Christopher, The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & The Rise of Chinaphobia (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2014)

Haywood, Ian, Working-class Fiction from Chartism to Trainspotting (Plymouth: Northcote House, 1997)

Janssen, Flore, and Lisa C. Robertson (eds), Margaret Harkness: Writing Social Engagement 1880–1921 (Manchester: MUP, 2019)

Knebel Doeberitz, Oliver von, ‘Muslims against Gays? Faith, Sexuality, Resistance and London’s East End’, in Ehland and Fischer, 185-200

Liggins, Emma, George Gissing, the Working Woman, and Urban Culture (New York and London: Routledge, 2017)

Maltz, Diana, Critical Essays on Arthur Morrison and the East End (New York and London: Routledge, 2022)

Marcan, Peter, An East End Directory: A Guide to the East End of London with Special Reference to the Published Literature of the Last Two Decades (High Wycombe: Marcan, 1979)

Marriott, John, Beyond the Tower: A History of East London (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2011)

Mayer, Ruth, Serial Fu Manchu: The Chinese Supervillain and the Spread of Yellow Peril Ideology (Philadelphia, PA: Temple UP, 2014)

Morrison, Kevin A. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of London’s East End (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., forthcoming 2022)

—–, Walter Besant: The Business of Literature and the Pleasures of Reform (Liverpool: LUP, 2019)

Newland, Paul, The Cultural Construction of London’s East End: Urban Iconography, Modernity and the Spatialisation of Englishness (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2008)

Palmer, Alan, The East End: Four Centuries of London Life (London: Murray, 2000 [1989])

Rubinstein, William D., Michael A. Jolles, and Hilary L. Rubinstein (eds), The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Sandhu, Sukhdev, London Calling: How Black and Asian Writers Imagined a City (London: Harper Perennial, 2004)

Seed, John, ‘Limehouse Blues: Looking for Chinatown in the London Docks, 1900–40’, History Workshop Journal 62 (September 2006), 58-85

Thomas, Susie, Andrew Whitehead, and Ken Worpole (eds), So We Live: The Novels of Alexander Baron (Nottingham: Five Leaves, 2019)

Valman, Nadia, ‘The East End Bildungsroman from Israel Zangwill to Monica Ali’, Wasafiri 24.1 (2009), 3-8

—– and Eitan Bar-Yosef (eds), The ‘Jew’ in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Culture: Between the East End and East Africa (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

Witchard, Anne Veronica, Thomas Burke’s Dark Chinoiserie: Limehouse Nights and the Queer Spell of Chinatown (New York and London: Routledge, 2016 [2009])